|

| Classic Performance Products |

| Tri-Five Straight Axle Clip |

| By Mike Harrington |

|

|

|

Here at Super Chevy magazine we have received numerous

e-mails from readers asking how to build a straight-axle Tri-Five. It seems

that over the past decade or so, the nostalgic gasser look of the '60s has

returned with a vengeance.

We won't bother going into the history of gassers in this

article. Suffice it to say the gasser look and stance was all about weight

transfer at the track. We put out the call for anyone doing a straight-axle

install, and a year or so later found ourselves heading up to Clearfield,

Utah.

The guys at Salt City Speed Shop (SCSS) answered the call

and let us stand over their shoulders as we documented them installing a

Jim Meyer Racing straight-axle conversion kit. |

The crew at SCSS was in the middle of setting up a new shop

location, so we moved the installation of the front clip to a more familiar

setting-the family home garage. To tell you the truth, during the course

of the install we kept expecting things not to fit quite right or run into

some sort of problem. It never happened. On several occasions, SCSS's Kris

and Larry Elmer commented on how well-engineered the Jim Meyer clip was.

The '55 Chevy rolled into the shop, and five days later it rolled out of

the shop, complete and ready. Due to the length of this install article

we are going to jump right into the specifics. What you see is what you

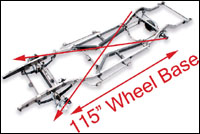

get. The rear-steer leaf-spring suspension includes everything you'll need

to install it into a stock 115-inch wheelbase Tri-Five frame. |

The straight axle assembly is complete with tube axle (any

width), leaf springs (rated at 3,500 pounds for the pair) with front shackles

and rear-frame brackets, shocks with frame-mount brackets, new Super Bell

early Ford spindles with bolt-on Super Bell 2-inch dropped steering arms,

new cross-steer Vega steering box with 2-inch dropped Pitman arm and cross-steer

drag link and tie-rod. It features Wilwood 4-piston calipers with 10 3/4-inch

rotors with a 5-on-4 3/4 wheel-bolt pattern to fit inside nostalgic 15-inch

wheels. Included are box tube grafting sections to install the new suspension

to the stock chassis that will be cut at the first body mount, just in front

of the firewall. Also in this subframe kit are steering linkage hook-up

kits or new ididit steering columns and disc/drum brake kits that plumb

into your existing brake system. |

|

| The first obvious steps were to start dismantling the entire

front end of the vehicle. During the dismantling process, the guys at Salt

City Speed Shop tagged and bagged every nut, bolt, and wire. It helped prevent

migraine headaches during the reassembly. |

|

|

| Larry Elmer, Kris's father, sparked up the blowtorch to cut

loose some rusted and stubborn bumper bracket bolts. Penetrating oil did

nothing to release the fused bolts, so this was a last-resort measure. |

|

|

| Progress is being made. The front sheetmetal was removed and

set off to the side. Now it was easier to look at what might be hiding under

the skin of this vehicle. |

|

|

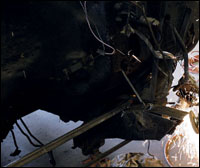

| Kris Elmer was amused after taking a close look at the Chevy

frame. It was in bad shape. The frame was cracked in two different places,

and the driver's side spindle was bent, causing some serious negative caster

issues. The passenger's side of the frame was also bent and had some horrible

negative camber issues. In short, it was sort of like a pretzel frame. If

ever there was a candidate for a straight- axle install, this former wheel-hopping

'55 was a perfect choice. There was no saving this front end. |

|

|

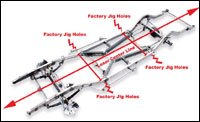

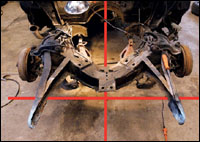

| This photo is actually of a complete Jim Meyer straight-axle

chassis. We couldn't find photos of a bone stock frame, so we used this

one to illustrate the measurements taken. SCSS didn't trust any of the measurements

from the misaligned frame, so the guys chose a different method. Typically

one would establish the wheel alignment and position by the wheelbase of

the vehicle in question. In this case, the '55 Chevy had a 115-inch wheelbase.

Measuring diagonally from corner to corner in the center of each hub is

the typical method for determining where the new wheels and axle will sit. |

|

|

| Here's how they did it. First they located the factory jig

holes on the frame in the front and the back. A measurement using the jig

holes as a reference point was taken from left to right in the back, and

from left to right in front. Then the center of these jig hole measurements

was established. Luck was on our side-when the laser sight was used, the

centers lined up perfectly. We now knew the rest of the frame, minus the

front, was accurate and in good shape as far as alignment goes. We then

measured 115 inches from the center of the hub on the rear axle to the center

of the front hub on both sides of the vehicle in order to determine the

factory wheel position and centerline. That factory wheel position was where

we planned to install the new straight axle. We all like altered-wheelbase

cars, but not an accidental altered wheelbase through poor measuring. |

|

|

| Using a plumb bob and micrometer to check the hub centerline,

the SCSS crew made one more measurement, using the traditional diagonal

measurement style to double check themselves. |

|

|

| After all the measurements were taken, checked, and re-checked,

a marker was used, and the horizontal and vertical lines were drawn on the

floor for future reference. Since the car was on jack stands and leveled,

there were no worries about where to place the new axle and wheels. |

|

|

| Now the fun begins. Kris used a plasma cutter to snip the

front of the '55 off. This is the point of no return; if we weren't committed

in the beginning, we sure were now. |

|

|

| When the front of the original frame was cut off, it was deliberately

cut too short. More metal can always be trimmed back to fit the new piece.

The new straight axle clip was placed under the frame and mocked up in order

to see how much more metal needs to be shaved off. |

|

|

| After further cutting, this is the result. More was taken

off the bottom than the top, and this gave us some wiggle room for leveling

the clip. |

|

|

| The very ends of the new clip were also clearance-cut in order

to make it easier to fit into the channels in the old frame. |

|

|

| Once again the same methodical process of measuring, using

a laser level and plumb bob are used in order to match the new frame to

those of the previous measurements. The frame and axle center were aligned

to the measurements and lines that were drawn on the pavements surface.

After the vehicle is built, the only wheel alignment that can be performed

is toe in or toe out. Prior to the finished product, all alignment has to

be built into the suspension. The reason for all the re-measuring is to

take into account all the tolerances of the new frame. The geometry of the

new parts needs to match the geometry of the old. Once all that is figured

out, it's full steam ahead. |

|

|

| Now the frame can be tacked into place and checked again if

need be. |

|

|

| In order to provide more support to the weld joint, a small

patch panel was fabricated by the shop and tacked into place just behind

the spring bracket. This added surface area for the weld will greatly increase

the frame strength. We later found out that these pieces were included in

the kit, but were somehow missed. |

|

|

| Now that the entire front clip is welded into place, Kris

and Larry assembled and mocked up the rest of the components to see just

how everything would align. In this photo you can see what looks to be two

possible spring locations for height. However, the lower hole is the correct

size and location. The center hole is there for looks. |

|

|

| The Super Bell axle and spindles were also temporarily assembled

and installed. Just like the springs, the axle also has two possible locations.

The axle can be set on top of or below the springs. Below the springs will

give the front end a higher ride height, while on top of the springs will

give it a lower altitude. Since the springs were installed higher, it was

decided to install the axle to bring the height down by a few inches. |

|

|

| Before any of the steering was assembled, here's where we're

at: First off, it was amazing to watch the methodical installation performed

by Kris and Larry Elmer. Every part in the Jim Meyer kit worked exactly

as it was supposed to work. During the install and assembly, Larry Elmer

kept remarking what a well-engineered set up Jim Meyer made. Back in the

day, Larry built a straight-axle '55 Chevy from scratch. He said our five-day

project took him two months back then. |

|

|

| While the Jim Meyer subframe comes complete with a Vega steering

box, we used one of Classic Performance Product's (CPP) units. We also got

the optional telescoping double D steering shaft, Borgeson U-joints and

ididit column from CPP, which had them on the shelf and readily available

for next-day delivery to our shop in Utah. You can also purchase the item

directly from Jim Meyer. |

|

|

| No need to worry about drilling holes into the frame for the

Vega box. |

|

|

| The ididit column from CPP went in like it came from the GM

factory back in 1955. |

|

|

| Once the column was in, the double D shaft was trimmed down

and the Borgeson U-joints are installed on the shaft. It turns out we didn't

need to use the telescoping shaft. There just wasn't enough room. |

|

|

| The one thing that didn't come in this kit was brackets for

the brake hose. Kris did a splendid job at fabbing up a set. |

|

|

| Once everything was assembled, the engine was installed to

weigh down the suspension and check out the work that was performed. After

this, it was all taken apart again while more finishing touches were added.

Even the headers cleared the steering shaft. Score one for us-that's one

less headache to deal with. |

|

|

| With the engine pulled out, it was time to set the caster

angle of the axle and spindles. We called the Jim Meyer tech line and asked

them what they recommended. We were told to set it between 5 and 8 degrees.

We set it at the maximum of 8 degrees. |

|

|

| With the caster set, the spring pads were TIG-welded into

place. As before, Kris would often switch sides while welding from left

to right in order to avoid heat buildup and warping the axle. |

|

|

| The last bit of welding that was performed on the frame was

the addition of some reinforcement plates. It couldn't hurt to make sure

the frame was solid as the Rock of Gibraltar. |

|

|

| The vehicle was rolled outside and the bare metal frame was

doused with self-etching primer, along with all the other parts. After the

primer dried, it was painted in a semi-gloss black. |

|

|

| While the paint was drying, Larry went ahead and assembled

the Wilwood brakes, packed the bearings, and made sure everything was ready

to go once the paint dried. The Wilwood disc brake system kit came with

everything we needed and went together with ease. These modern wonders are

going to help our '60s-look gasser safely stop like a much newer car. |

|

|

| In the meantime, Kris spent a fair amount of time custom-fabricating

and installing all the new brake lines and bleeding the system. This is

the final shot before the engine goes back in permanently. What a fantastic-looking

project this turned out to be. |

|

|

| All the sheetmetal is put back on and this is the view from

the front. |

|

|

| Here's that all-important nostalgic '60s gasser stance that

looks oh, so cool! The wheel placement is perfect-all that careful measuring

paid off. |

|

|

| After all the king's horse and all the king's men put the

Chevy together again, the only hiccup we ran into was the radiator position.

Notice how close it is to the pulley, leaving no room for the fan. That

problem was easily solved by moving the radiator to the other side of the

core support. Now it's time to uncork the headers and upset the neighbors. |

|

|